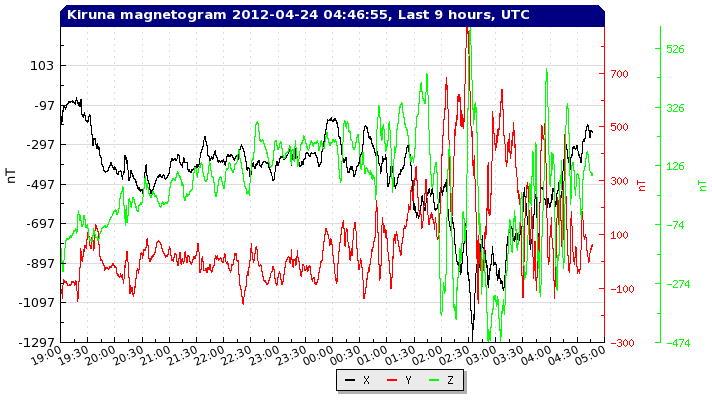

Magnetometr w Kirunie

This magnetometer gives you the values of the magnetometer stationed at The Swedish Institute of Space Physics in Kiruna, Sweden. It is often used in Europe to see if there is chance for aurora right now. If you are located outside Europe you should find another magnetometer which is closer to your location.

But how do we read this plot? The plot displays the X, Y and Z values that are being observed at the magnetometer in Kiruna. The line of interest is the black line. It represents the X-component which represents the magnetic field strength in roughly the direction of the north magnetic pole. When the Earth's magnetic field is calm and the geomagnetic conditions are at very quiet levels we will see a value of about 10685 nanoTesla (nT) for the X-component on the Kiruna magnetometer. However, when the magnetic field becomes disturbed due to enhanced space weather conditions, we will see that the values on the graph will start to fluctuate and those values are important for us to determine if there is a chance to see the aurora. During geomagnetic storming when Kiruna is on the day light side of the Earth, the Kiruna magnetometer could show deflections higher than the baseline of 10685nT. This is normal because on the day light side of Earth, the magnetic field is being compressed by the incoming solar wind.

For the lower European middle latitudes like the southern England, Belgium, and central Germany you might be able to capture photographic aurora (not visible with the naked eye) when there is a deflection of at least 700nT on the Kiruna magnetometer. Visual aurora (visible with the naked eye) can be expected when the deflection is 1300nT or more. We understand that this might be complicated to understand so let's work with two examples.

At middle latitudes locations, like Belgium and The Netherlands, the most common form of aurora that we might see sometimes, are weak aurorae low on the northern horizon which might be hard to see with the naked eye. A good example of how the Kiruna magnetogram would look like in such a situation can be seen on the picture below. The deflection was about 1200nT and the predicted Kp-index at that moment was 7. We can conclude that weak visual aurora was possible for northern parts of The Netherlands and Germany.

A second (rather extreme) example is this magnetogram from 30 October 2003. Two coronal mass ejections from a X17 and X11 solar flare arrived at Earth and caused extremely severe geomagnetic storming with aurora which could be seen all the way in Portugal, Europe and Florida in the United States! At all middle latitude locations, the aurora was seen directly overhead! These storms will always be remembered as the "Halloween Storms of 2003" and were the strongest geomagnetic storms of SolarCycle 23 with a Kp-index of 9.

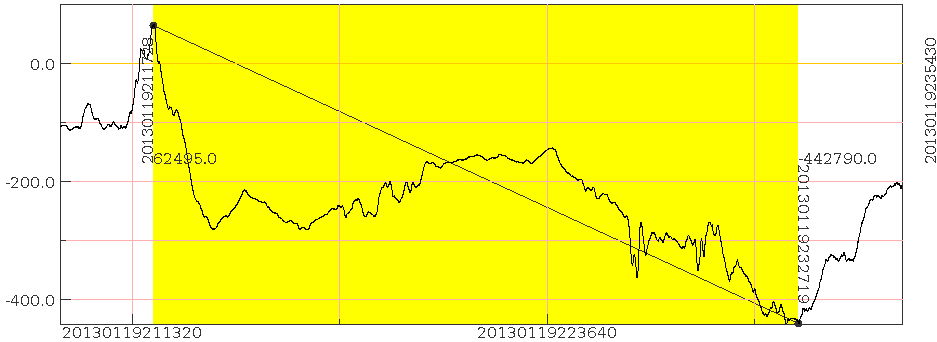

But how do we determine this deflection? When Earth's magnetic field get's disturbed, the magnetometers will react to it and thus the Kiruna magnetogram will show us minor deflections from the normal quiet level of 10650nT. This deflection is also expressed in nanoTesla units (nT). The start of this deflection occurs during the onset of a geomagnetic storm before the measured values start to drop. It's difficult to explain this in words so in the graph below you'll see a good example of a deflection, measured at the Kiruna station. The deflection is shown as a yellow area in the graph; it starts shortly with a spike after the arrival of the coronal mass ejection before it reaches it's lowest point. This deflection, expressed in nanoTesla, is the value we have to look at if we want to see or photograph the aurora. In this example the deflection is around 500nT and that is associated with a local Kiruna K-indice of 6 and thus was this not enough for aurora on the lower middle latitudes.

Interpreting the K-index based on values from Kiruna

Indeks K jest podobne do Indeksu KP, Indeks Burzy geomagnetycznej ze skalą logarytmiczną od 1 do 9. Indeks KP jest planetarnym indeksem łączący magnetometry z wielu lokalizacji dookoła świata, gdzie Indeks K tylko pochodzi z jednej stacji magnetometrów. Na podstawie odchylenia, które można obliczyć z grafu przedstawionego przez Szwecką instytucję Fizyki kosmicznej (IRF) możemy spróbować zdeterminować Indeks K z magnetometrów w Kirunie, Szwecja. Dla specyficznych stacji w Kirunie, robimy to za pomocą tabeli podanej poniżęj. Zwróć uwagę, że przez położenie te magnetometry są przydatne tylko do obserwacji w Europie. Jeśli się znajdujesz poza Europą polecamy znaleść innych magnetometrów, bliższych dla twojej lokalizacji. Miej na uwadze, że tabela jest tylko używana dla magnetometrów z Kiruny! Nie możesz użyć jej dla innych magnetometrów!

| Indeks K | Odchylenie w nanoTeslach | Typ burzy |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 - 15 | Ciche warunki |

| 1 | 15 - 30 | Ciche warunki |

| 2 | 30 - 60 | Ciche warunki |

| 3 | 60 - 120 | Niewyjaśnione warunki geomagnetyczne |

| 4 | 120 - 210 | Aktywne warunki geomagnetyczne |

| 5 | 210 - 360 | G1 - słaba burza geomagnetyczna |

| 6 | 360 - 600 | G2 - umiarkowana burza geomagnetyczna |

| 7 | 600 - 990 | G3 - silna burza geomagnetyczna |

| 8 | 990 - 1500 | G4 - poważna burza geomagnetyczna |

| 9 | 1500 i więcej | G5 - ekstremalna burza geomagnetyczna |

Aktualne dane sugerują, że istnieje niewielkie prawdopodobieństwo pojawienia się zorzy polarnej w następujących regionach o wysokiej szerokości geograficznej w najbliższej przyszłości

Gillam, MB, Yellowknife, NTNajnowsze wiadomości

Najnowsze wiadomości z forum

Wesprzyj SpaceWeatherLive.com!

Wielu ludzi odwiedza SpaceWeatherLive aby śledzić aktywność słoneczną lub sprawdzić czy jest szansa na zaobserwowanie zorzy polarnej. Niestety, większy ruch na stronie oznacza większe koszty utrzymania serwera. Dlatego, jeśli jesteś zadowolony ze strony SpaceWeatherLive, zachęcamy do wspierania nas finansowo. Dzięki temu będziemy mogli utrzymać naszą stronę.

Alerty

04:15 UTC - Aktywność geomagnetyczna

Aktywne warunki geomagnetyczne (Kp4) Osiągnięty próg: 03:57 UTC

02:30 UTC - Indeks mocy półkuli

Model OVATION przewiduje, że index mocy półkuli osiągnie 50GW o 03:23 UTC

środa, 16 kwietnia 2025

21:45 UTC - Aktywność geomagnetyczna

Słaba burza geomagnetyczna G1 (Kp5) osiągnięty próg: 21:36 UTC

21:00 UTC - Aktywność geomagnetyczna

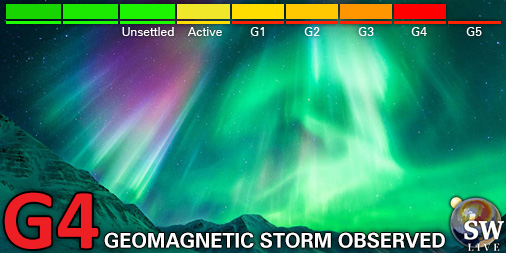

Bardzo silna burza geomagnetyczna G4 (Kp8) osiągnięty próg: 20:55 UTC

19:45 UTC - Aktywność geomagnetyczna

Silna burza geomagnetyczna G3 (Kp7) Osiągnięto próg: 19:25 UTC

Fakty na temat pogody kosmicznej

| Ostatnie rozbłyski klasy X | 2025/03/28 | X1.1 |

| Ostatnie rozbłyski klasy M | 2025/04/15 | M1.2 |

| Ostatnia burza geomagnetyczna | 2025/04/16 | Kp8- (G4) |

| Dni bez plam słonecznych | |

|---|---|

| Ostatni dzień bez skazy | 2022/06/08 |

| Średnia miesięczna liczba plam słonecznych | |

|---|---|

| marca 2025 | 134.2 -20.4 |

| kwietnia 2025 | 120.5 -13.7 |

| Ostatnie 30 dni | 118.3 -22.1 |